Fiscal responsibility must be matched with climate credibility

‘Unfunded’ carbon targets aren’t enough

It’s hard to deny that the public finances are not in a great state. Taxes are at their highest level in decades. Growth is anaemic. Inflation is stubbornly high. Interest rates are the highest they’ve been in a long time. And all the while, public services are declining from a lack of funding and investment.

In this environment, politicians across the board are keen to say that they won’t be profligate in their spending. Part fear of markets, part electoral strategising, Britain’s leading politicians are convinced that it’s simply not realistic for them to promise more public funding any time soon.

To show they’re serious, they like to pick out policies that they say they would really love to go ahead with, but that unfortunately they must push to one side in the name of fiscal rectitude. Even before the latest argument around London’s clean air scheme and the Uxbridge by-election, politicians were already considering scaling back promises to decarbonise the British economy. The most obvious and striking example was when Labour walked back on its initial indication of a big plan for green investments, drastically reducing the amount it said it might spend over the next parliamentary term.

This way of thinking about public investment and the national accounts is flawed and is in large part responsible for Britain’s lost decade of austerity.

However, this is where we are. So instead of going over that argument, I want to challenge Britain’s current and would-be leaders with a different proposition: treat our carbon budget in the same way you treat the regular budget.

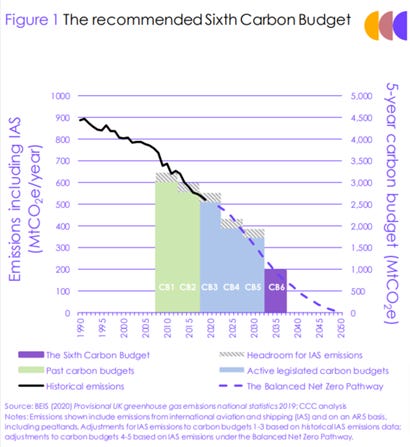

First, what is the carbon budget? This is a concept that is often used in climate change conversations to describe the amount of carbon emissions available to a country in order to hit its climate goals (or, sometimes, in order to stay within their fair share of the UN-defined global objectives).

In the UK, the official independent advisory body on climate change and emissions reduction, the Climate Change Committee, produces a regular update on our carbon budget. The most recent report, published in 2020, set out the decarbonisation path up to 2037, with the final goal of reaching net zero by 2050. It was this report that recommended going for a 68% reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 (relative to 1990 levels), which is the target that the UK then formally submitted at the UN.

But the carbon budget isn’t law. It requires policies to follow up and to turn the recommendations for the path to decarbonisation into reality. If politicians don’t deliver those policies, then we’ll simply blow right through our carbon budget limits and render those targets little more than meaningless numbers on a page.

Just as disregard for our fiscal position carries serious consequences, so too does a failure to rein in our carbon addiction. Earlier this month, scientists estimated that the world was subject to the hottest week since records began. Countries around the world are breaking their temperature records. Residents in US cities have had to start thinking about outdoor smoke levels. The city of Milan swung from a heatwave to a hailstorm in a matter of days. Spain’s farms are drying up. Tourists and residents have had to flee the island of Rhodes as wildfires take hold. All around the world, the climate crisis is escalating – and it won’t stop anytime soon.

Even if you’d rather ignore the problem unfolding before our eyes, inaction on climate won’t be free. Whatever is saved on climate mitigation (policies to cut carbon emissions), just as much will be needed for climate adaptation (the cost of adapting to climate change). Would the mass installation of air conditioning to fight deaths during heatwaves be any cheaper than converting gas boilers to heat pumps? What about building houses to resist new weather extremes? Or the addition of flood defences to areas that have never needed them before?

This then is the choice that politicians are presented with: do they commit to delivering policies that will keep us within the carbon budget (with the obvious consequences for public spending) or do they change our climate targets (with consequences for the wellbeing of our country, continent and planet)?

Because to avoid this choice simply isn’t credible. There’s no realistic way that you can ease off from decarbonisation policies today and maintain our 2030 and 2050 targets. Any party’s policy on climate change must either put forward the necessary policies and funding (i.e. much more than today) or explain what they think the new climate targets should be and why we don’t really need to reach net zero by 2050.

For surely any politician that declares they are unwilling to make spending promises without attached funding must also, by the same logic, be unwilling to promise carbon cuts without the policy framework to get there.

Indeed, if anything, the rationales of fiscal responsibility – that there’s no magic solution, that we must live within our means, that we mustn’t burden future generations – apply far more accurately to carbon credibility.

Fighting climate change isn’t simply another giveaway or nice-to-have - it’s the fundamental issue facing this generation and multiple generations to come. If governments or parties wish to kick that can and delay the inevitable costs to another day, then let them say so. Alternatively, they will have to explain that some spending and taxes will be higher and that some things won’t continue as before. But one way or another, politicians that pride themselves on making the hard choices and on being straight with the public must present policies that are carbon credible – and face the consequences from voters.